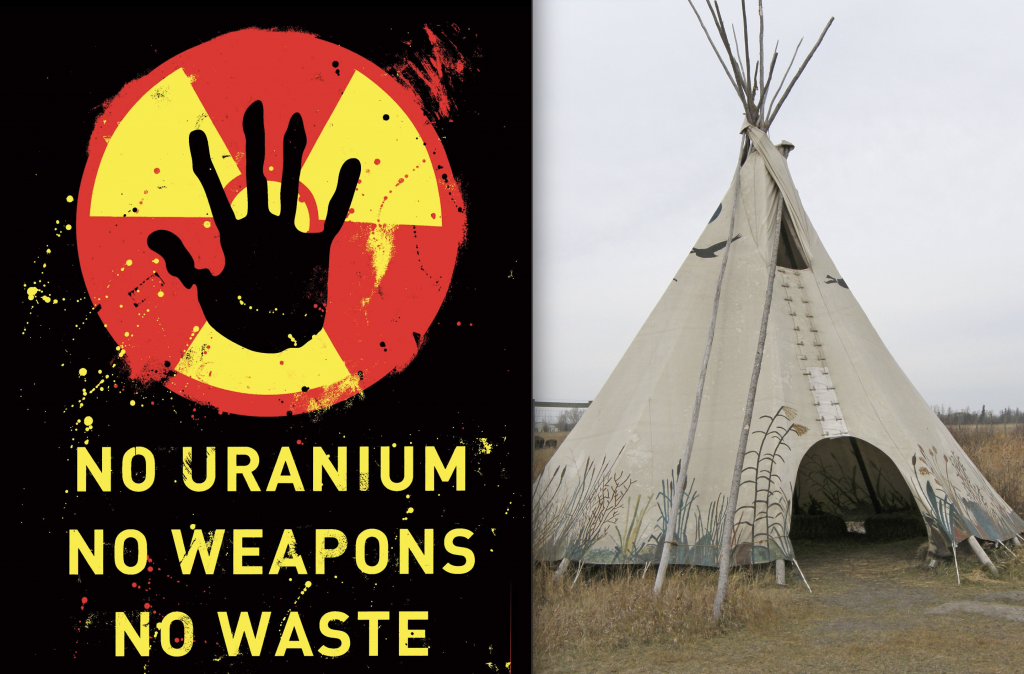

Dust-up: First Nations Group and Uranium Co. Clash; Teepee Blockage Goes up, Mining Co. Backs down

(EnviroNews World News) — A dispute between a uranium company and a Canadian First Nations group in Saskatchewon heated up when a crew from the company was found surveying tribal lands about 600 miles northeast of Saskatoon in early February. “First Nations” is the term used by the Indigenous people of Canada and the government to describe those persons who are not Metis or Inuit and whose ancestry can be traced to the original inhabitants of Canada. Birch Narrows Dene Nation, which has a population of about 800 people, erected a teepee blockade to stop the interlopers from Baselode Energy Corp. from working along their traplines without consent. The First Nations people also issued a cease-and-desist order according to the CBC.

The dispute took place at the edge of the Athabascan Basin where some of the world’s richest uranium ore is found. The area is also home to endangered animals, including boreal woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) and Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis). Birch Narrows trapper and elder Ron Desjardin, who discovered the surveying crew, contacted Birch Narrows Chief Jonathon Sylvester to see if the crew was authorized. Sylvester said they were not. When Desjardin spotted the workers again a few days later, he told them they shouldn’t be there, especially since there was a COVID-19 lockdown in effect.

“That really was infuriating because it was just so disrespectful. Just total disregard,” Desjardin said. “We’re not back in the 1800s anymore. They can’t do this stuff to us.”

Desjardin and Sylvester expressed their frustration because the company originally seemed to be negotiating in good faith. It offered to build a cell phone tower for Birch Narrows, but Desjardin told Baselode representatives it wasn’t a priority project. The tribe wanted a detailed wildlife and habitat impact study before any work proceeded. Desjardin said:

As a trapline area, we carry out extensive activity: trapping, hunting, fishing. We’ve done it for generations. It’s been passed down to us for a long, long time. We have people who have passed away on those traplines, who have given up their lives on those traplines in their struggle to feed their families. That area means a lot to us. It’s not just an ordinary piece of land. It has a lot of significance to us as a community.

Stephen Stewart, the Chair of Baselode’s board, said the company needed to start the survey because the work had to be done while the ground was frozen. He also acknowledged the job could have waited for a week while the company negotiated with Birch Narrows.

“In any project that is in the extractive business, you absolutely need to have these local communities as partners. Not to be cliché, but it is a win-win for everybody,” said Stewart. “I will note that we are permitted to do this work, but permit and the consent of the community are different things.”

Lawyer and University of Saskatchewan Lecturer Benjamin Ralston said Canada’s Constitution and emerging case law require First Nations concerns must be front and center on any development affecting them.

“Certain behaviors or ways of doing business that might have worked in the past no longer work, based on a more robust understanding of how treaty rights and aboriginal rights need to be reconciled,” Ralston asserted.

While the teepee blockade has been removed, other First Nations peoples in Saskatchewan are throwing their support to the Birch Narrows Dene Nation. Leaders from Little Pine First Nation, Meadow Lake Tribal Council, Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations are among those that have issued statements regarding Baselode’s faux pas.

“The province needs to provide the already underfunded First Nations with the financial resources to be able to participate at the table in a meaningful way,” said Meadow Lake Tribal Council Tribal Chief Richard Ben. “Otherwise, many First Nations will be left out of the process. We can’t undertake studies at our own expense in order to be consulted on resource development within our territory.”

Stewart promised the project will not proceed unless the First Nations agree. “There can be no project without the buy-in from the communities,” he concluded.

FILM AND ARTICLE CREDITS

- Shad Engkilterra - Journalist, Author