Tule Elk Wars: Was Ranching Really Meant to be Forever in Point Reyes National Seashore? (EnviroNews Investigative Report)

(EnviroNews Nature) — Inverness, California — A wildlife and public lands conservation battle is raging over the Point Reyes National Seashore (PRNS/the Seashore/the park) in Northern California’s Marin County as citizens, activists and some of the country’s most prominent environmental groups have been fighting tooth and nail, in an effort to compel the federal government to evict two dozen cattle ranches from the West Coast’s only national seashore. The Seashore is home to one the largest remaining herds of tule elk (Cervus canadensis nannodes) — an ungulate endemic to California and a species that hovers at one percent of its historic numbers.

When the park was forged nearly six decades ago, the ranchers were paid millions for their properties and given a “reservation of use and occupancy” (RUO/ROU) — terms that expired after 25 years, or death in some cases. But the ranchers and their heirs are still there and they’ve just been given a new lease on life — quite literally. Yet, one question continues to burn: was ranching supposed to come to an end, or was it meant to roll on in perpetuity at PRNS? A 13-month-long investigation by EnviroNews Nature gets to the root of that issue.

BACKGROUND: RECENT, RELATED AND RELEVANT NEWS RUNDOWN

On Sunday Sep. 13, 2021 — on the eve of PRNS’ 59th birthday — over 300 protestors threw down again — this time, in front of the National Park Service’s (NPS/Park Service) Bear Valley Visitor Center, putting the Park Service on blast and imploring the Biden Administration to give the ranchers the boot and restore the area. This all went down on the day before the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI/Interior) — under Secretary Deb Haaland — hit the deadline for a decision on which path the government would take in its mandate to update the Tule Elk General Management Plan for PRNS.

Anticipation had been building for two months after DOI asked for an extension to evaluate the issue further. But the next day, Monday Sept. 14, the protestors received the devastating news from the Park Service: 20 more years for the ranches, more fences, permission to establish stores and bed and breakfasts and a general management plan (GMP) that allows for the shooting of tule elk in the Seashore’s Drakes Beach herd.

“This plan strikes the right balance of recognizing the importance of ranching while also modernizing management approaches to protect park resources and the environment,” said Craig Kenkel, Superintendent of Point Reyes NPS, in a news release surrounding Interior’s official Record of Decision (ROD). Shannon Estenoz, Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Fish and Wildlife and Parks added, “Point Reyes National Seashore protects diverse natural and cultural resources that can serve as a model where wilderness and ranching can coexist side by side.” Thousands of now-outraged citizens fervently disagree with both those statements.

Legal Dust-up: Non-Profits Sue, Forcing the Interior’s Hand as More Legal Actions Loom

NPS, an ancillary agency under the Interior, was forced to conduct a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)-mandated environmental impact statement (EIS), after three conservation non-profits teamed up and sued the government over damage they say agricultural activities are having in the park. The Seashore is home to a plethora of critters and creatures, including multiple threatened, endangered or imperiled ones. The three plaintiffs in the lawsuit are the Center for Biological Diversity (the Center), Western Watersheds Project (WWP) and Resource Renewal Institute (RRI).

WWP and RRI were co-sponsors in the Sept. 13 protest, alongside In Defense of Animals, Turtle Island Restoration Network (TIRN), Save the Tule Elk, Restore Point Reyes, and Restore and Rewild Bay Area. WWP and the Center are two of the most formidable conservation groups in the United States, with both NGOs boasting a success rate of over 90 percent when suing the federal government in wildlife cases. Erik Molvar, Executive Director with WWP told EnviroNews, “Given the focus of the new plan on livestock production, rather than protection, preservation, and public enjoyment, [further] legal action is a strong likelihood.”

Biden-Haaland Fall Directly in Line with the Trump-Bernhardt Plan

As part of the NEPA process — under the Trump Administration’s then-NPS de facto Director Margaret Everson — the agency issued six draft alternatives for the Tule Elk General Management Plan: A-F. At the opposite ends of the spectrum were Alternative B, which offers the ranchers non-compete 20 year lease extensions and manages tule elk to minimal numbers by lethally culling them, and Alternative F, which called for the removal of all ranching activities, fencing and livestock infrastructure from PRNS.

Trump-Bernhardt-Everson announced their preferred choice: Alternative B — a plan considered draconian by many in the conservation movement. Environmentalists had been on the edge of their seats for months, watching and waiting to see if a new Interior Department — run by the nation’s first-ever Native American presidential Cabinet member — would do something different. They were sorely disappointed. Outrage continues to ripple through the movement as protest leaders tell EnviroNews the fight is far from over. “Alright motherfuckers, it’s on!” one community organizer told EnviroNews after learning of the Interior’s decision, asserting that the move would only strengthen their resolve.

The “elktivists,” as they have come to be know, had been holding out high hopes for Haaland, imploring anyone from NPS who would listen to forget about Trump-Bernhardt-Everson’s Alternative B and to pick a more environmentally-friendly course of action instead.

In the waining weeks and days of the Trump presidency, his administration implemented a swath of Earth-shattering rollbacks and rule-changes that shafted imperiled species and gutted several underpinning pillars of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) itself — a bedrock piece of legislation that polls have shown over 80 percent of the public supports. But straight away, when Biden took over, his administration went on a tear, overturning and reversing a number of those Trump rule-changes, leaving elktivists hopeful that Biden’s Interior Department would do something similar for PRNS. But to their dismay, Biden’s Interior fell right in line with the Trump Administration’s plan for Point Reyes.

PRNS was birthed from a unique situation: it is a national park unit forged by way of the government acquiring private lands. Now, in the wake of NPS’ decision, the question still remains: was ranching at the Point Reyes National Seashore intended to go on in perpetuity from the Seashore’s inception or not? There is passionate disagreement over that topic. Below in this in-depth report, EnviroNews asked several prominent people involved with this issue to weigh in. Their opinions vary widely on whether Point Reyes ranching was supposed to be a “forever-thing.” But by the bottom of this investigative report — which includes both written and embedded video content — we arrive at the bottom of this burning issue.

FIRST, ARE THESE RANCHES REALLY ‘HISTORIC?’

So, are the ranches at PRNS truly historic? That all depends on who you ask. Certainly, there are no shortage of old cattle operations in the area at large. But many of the ranches here weren’t recognized and listed in the National Register of Historic Places until 2018, long after the formation of PRNS. But the ranchers, the area’s lawmakers and Point Reyes NPS itself all argue that these operations are bedrock and should remain — despite a strong sentiment from tens of thousands of people that they should be evicted without further ado (more on that shortly).

The words cattle ranching and national park (or national seashore in this case) might seem a strange couple to be paired together in the same sentence, but that’s how it’s been at Point Reyes for decades. PRNS is a one-of-a-kind NPS unit and these agriculture operations have been present since the Seashore was formed — and they don’t want to leave. Now, nearly 60 years on, opponents say the ranchers were paid a fair price for their land — by some estimates, as high as $370 million in today’s dollars — and that their deal to continue operating was a temporary one. The ranchers on the other hand say they feel they’re entitled to stay indefinitely as part of a “historic” component of the Seashore’s legacy.

The word history has been shown to be a very subjective thing, as in: whose history? Who is telling the tale? The oppressed and the oppressor will always write a different version of events. And there’s multiple accounts of the story here at Point Reyes as well.

DEEPLY EMBEDDED: A STRONG LOBBY IS AFOOT

The ranching families — around two dozen of them (or as few as 14 by some assessments that claim there has been interbreeding amongst the families) — along with other homeowners in the area, were paid for their properties, and given time to relocate or wind down their operations. The ranchers were given the RUOs — special use permits that allowed them to stay up to 25 years, or in several cases, until the death of the leaseholder/s. Most of the RUOs were coming to an end by the 90s, yet the ranches are still there. But how?

In 1999, the Interior Department issued a clarifying briefing statement to Congress, stating, “National Park Service policy, NPS-53, clearly prohibits an extension of a Reservation of Use and Occupancy,” reinforcing that if livestock operations were to continue in the Seashore, it would have to occur by way of leases and/or permits.

An amendment to the original park legislation, passed in 1978, opened the door for the continuation of ranching in the park. When the RUOs began to expire, NPS started issuing the ranches five-year leases and permits. Meanwhile, conservationists argue the continuation of ranching in PRNS violates the law on multiple fronts.

Nevertheless, since those RUOs started expiring, Point Reyes NPS has granted these cattle operations extensions time and again, carrying them up to the present day. But why?

In the Pacific Sun, local investigative reporter Peter Byrne makes this point:

Tens of thousands of acres of ranch-lands in West Marin and Point Reyes National Seashore are controlled through deed or lease by members of the Grossi, Mendoza, McClure, Kehoe, Evans, Rossotti, Giacomini, Dolcini, Strauss and Spaletta clans.

Family members wield considerable political power through organizations such as Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT), Marin Board of Supervisors, Marin County Farm Bureau and the Point Reyes Seashore Ranchers Association.

In other words: there’s a strong lobby afoot. Meanwhile, the RUOs also carry specific conditions — terms critics say the ranchers have no way of abiding by. Byrne continued in the Pacific Sun, “Notably, NPS-53 prohibited the issuance of permits that ‘conflict with other existing uses.’ Elk grazing, for example.”

Still, opinions vary widely on what actually constitutes a historic element at the Seashore. But, for the original inhabitants of the land here, the old history doesn’t paint pictures of cattle or dairies at all — or even European settlers for that matter.

ORIGINAL INHABITANTS: THE COAST MIWOK OR EUROPEAN PIONEERS?

This isn’t just a story about whether the Seashore should be converted to unadulterated wilderness as many people would expect to see when entering a national park unit. There’s a deeper underlying issue here and it involves the original inhabitants of the land: the Coast Miwok people.

To the Coast Miwok, the Seashore ranchers are Johnny-come-latlies. Jason Deschler, Dance Captain and Headman for the Coast Miwok Tribal Council of Marin (the Council), reminded attendees at the Sept. protest that his ancestors, alongside other “brown people,” built the PRNS ranches for European pioneers, after the land was plundered from them.

“In the 1950s, my family was evicted by ranchers [James] Lundgren and [Salyes] Turney,” exclaimed Theresa Harlan at the protest. Harlan is a descendent of the Jemez, Domingo and Laguna Pueblo Tribes, who was adopted by the Coast Miwok.

Harlan explained to the crowd that even though her family was expelled from Felix Cove it “did not sever their connection to [Tomales] Bay.” Backed up by cheers of support and affirmation, Harlan elaborated:

I think we all want to go home. We all want to go to a national park that will greet us in the spring with the fragrance of strawberries — wild strawberries. We want to return home to a park where we can learn about the Felix family and Native resilience. We want to return home to a park where we’ll learn the names and sites of Coast Miwok villages. We want to return home to a park where just so many yards back there, we’re going to hear song, prayer, dance [and] ceremony at Kule Loklo — at the roundhouse.

“The Coast Miwok Tribal Council of Marin needs to be front and center,” Harlan insisted to the onlookers and participants. But according to Dean Hoaglin, Headman and Dance Captain of the Council, the exact opposite is the case. Hoaglin sat down for an on-camera interview with EnviroNews this fall and said the Coast Miwok have been excluded at nearly every juncture in the planning process.

“The thing that I’m bothered by is the fact that we were not at the table,” Hoaglin told EnviroNews. “We were not invited to have a voice. As indigenous caretakers, and having that tribal ecological knowledge, it would make sense for us to be at the table.”

Hoaglin continued to EnviroNews:

Not to pick on any one group, but we’re talking about the ranchers right? How they were gifted this extension, in the name of what? Have they been the best, I guess you could say, land stewards? I don’t see that, because there are so many environmental issues that go along with it that they haven’t been held accountable… To me, [Alternative B] was almost the worst thing that could happen.

For the Coast Miwok, it’s not only NPS and the Interior that have failed to include them “at the table” though; Hoaglin says it’s some of his own relatives too. The Coast Miwok are not a standalone federally recognized tribe, rather, the band gains its status through Graton Rancheria — a federation of Northern California tribes and bands that Hoaglin acknowledged is dominated by the Pomo. When asked, “Are Graton Rancheria and the Coast Miwok on the same page, as far as what should be done with Point Reyes and how it should be managed?” Hoaglin said this:

As far as I’m aware of, no. And that’s unfortunate, because we’re all related.

And when asked, “[Is the Coast Miwok] getting a seat at the table with Graton Rancheria?” Hoaglin replied:

Not currently, but I would welcome that to happen — that opportunity. I welcome that invitation. That would please me.

“It’s disheartening though, that we wouldn’t be invited,” Hoaglin expressed. “I hope that that changes, because I believe in us coming together and staying united.”

Holding out Hope for Haaland

The Coast Miwok had been holding out hope for Deb Haaland too. On June 3, 2021, the Council even wrote her a letter imploring America’s first Native Cabinet member to rescue PRNS. Hoaglin told EnviroNews the Secretary hasn’t responded personally yet, but said with a smile that he welcomes that phone call.

“The Park Service is trying to erase Indigenous history in service of promoting the myth that cattle ranching was the original land use of Point Reyes,” Jeff Miller said in support of the Council’s letter back in June. Miller is a senior conservation advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity.

In another effort, citizens gathered more than 100,000 signatures in a letter to the Secretary, demanding her to heed the call to remove cattle operations from the Seashore. And they didn’t just mail it either; environmental activist Diana Oppenheim drove it all the way to Washington DC and hand-delivered it to the Secretary’s office. But it’s been crickets from the Interior Department on that letter as well.

In August, Secretary Haaland appeared in Northern California with the area’s Congressman Jared Huffman, who has been under heavy fire from constituents for his support of continued ranching in the park. The two of them toured Humboldt County’s Redwood National and State Parks together and shared in a lot of conservation talk. Haaland even called Huffman her “buddy” and gave him a shoutout for being her “mentor” in the Natural Resources Committee when she was new in Congress. Still, not a peep was uttered about the consequential, then-impending decision on the Tule Elk General Management Plan. EnviroNews covered the Redwood Parks tour, and in an exclusive story showed the Secretary being moved to tears when the local Yurok Tribe gave her a gift. But as for the Coast Miwok of Marin, they have received no such heart-warming moment with the Secretary to date.

Hoaglin made it clear that the Coast Miwok have been fighting an uphill battle — even with Graton Rancheria, in what he referred to as a “politically challenging” situation. Graton Rancheria, as a whole, has not opposed the ranching at PRNS. But historically speaking, the Seashore wasn’t Pomo territory either; it was inhabited by the Coast Miwok, leaving a rift between the Coast Miwok Tribal Council of Marin and Graton Rancheria over this hotly contested issue.

Also noteworthy, on Aug. 10, 2021, just a few weeks before the Tule Elk GMP RoD was released, Haaland announced a “first of its kind,” “government-to-government” deal between Graton Rancheria, the Interior Department and NPS. “The 20-year General Agreement is believed to be the only one of its kind in the country,” NPS boasted on its website at the time. Contained within that deal is written language that enacts a multi-party consultation strategy for management of the Seashore, as well as the indigenous artifacts and ranches contained therein. The agreement states:

The ranch lease program within the park and park management over these leases is an area of importance to the [Graton Rancheria] Tribe and to the vitality and restoration of the Tribe’s ancestral lands. Therefore, in accordance with the government-to-government partnership, consultation and coordination is critical to ensure Tribal views and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) are part of the management of these ranching leases and lands.

But even though the agreement mentions the Coast Miwok, along with the Pomo, atop the deal — creating the appearance that the Coast Miwok of Marin were part of the process — Hoaglin says the opposite is true and that the Council was totally excluded. He’s also concerned NPS may attempt to hide behind the deal for PR purposes, acting as if the Coast Miwok are in alignment with NPS management strategies for the Seashore, when they are not.

“We as Coast Miwok direct decedents, we still are the most likely decedents (MLDs),” Hoaglin, who is from the Hookooeko people, explained to EnviroNews. “But the federal government, the National Park Service, they don’t understand that, or they’re not adhering to that fact.”

Whose History? Mine or Yours?

Long before Spaniards and other Europeans could even conceive of building large ships and sailing across the ocean to new lands, in a time when they still thought the Earth was flat in fact, the Coast Miwok were flourishing in the area now encompassing Marin and southern Sonoma Counties. They were master hunters, gatherers, fishers, trappers, weavers and shelter builders. They were artists and ceremonialists. Amongst many other endeavors, they harvested and stored acorns and kelp and utilized tule grass (Schoenoplectur acutus), and tule elk as well, to sustain their lives. But that all changed of course when pioneers inundated the area, flocking there in droves, livestock in tow.

Finally, EnviroNews asked Hoaglin if ranching inside the PRNS is “historic” as the Park Service, the ranchers and other proponents of Alternative B claim? To that, he responded with several questions of his own:

What is historic in any one person’s perspective? Comparably, historic of what, 150 years? As compared to tule elk, since time immemorial? Such as us?

A nearly irrefutable fact: the history of the land that now comprises the Point Reyes National Seashore looks very different over the past two centuries, depending on who is telling the tale. And different versions of that history are being written to this day.

SO, WAS RANCHING AT PRNS SUPPOSED TO BE A FOREVER-THING? THE TRUTH PLEASE!

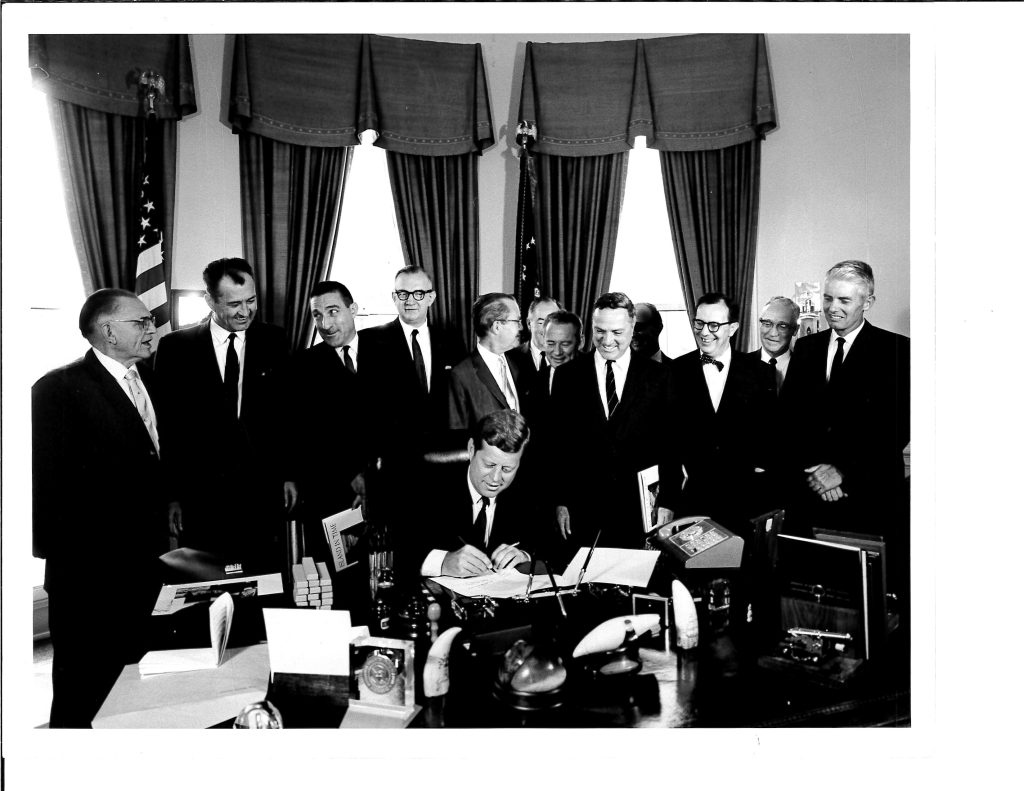

When PRNS was designated by Congress and made official by President John F. Kennedy’s pen in 1962, there was a not-so-small problem: there were still a couple dozen old cattle ranches — both beef and dairy — sitting smack-dab in the middle of the Seashore, and most of them weren’t wanting to hang up their hats and move away for a national park. Opinions vary starkly on what was ultimately supposed to happen with these enterprises. As part of an expansive, ongoing documentary film project, EnviroNews spoke with several prominent figures connected to the issue to take a deeper look. Short video excerpts of those interviews have been included in the body of this article to provide supporting information.

Former Obama-era Director of Foreign Disaster Relief/Former PRNS Assoc. Exec. Director: ‘This is One of the Most Hard-Hit Myths’ That Point Reyes Ranching Was Meant to Be ‘Forever’

Mark Bartolini is a disaster relief expert who served as the Director of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) under President Barack Obama. Amongst other Obama-era campaigns, he oversaw efforts during the cholera epidemic in Haiti, famine in Somalia, and the 2011 tsunami and nuclear meltdowns at Fukushima Daiichi in Japan. Before taking his post with USAID, Bartolini had a busy career at the International Rescue Committee (IRC) where he headed relief efforts in the Bosnian War and led other humanitarian campaigns in war zones including Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Myanmar. He’s a native of Inverness, California, where he still resides.

But humanitarian work and disaster relief aren’t all Bartolini is known for; he also used to be the Executive Director of the Point Reyes National Seashore Association (PRNSA), and he says some other living creatures are in need of relief as well: the Seashore’s Tomales Point tule elk herd.

When asked if ranching was intended to roll on endlessly in PRNS, Bartolini doesn’t hold back. “So, this is one of the most hard-hit myths that they’ve perpetrated: that it was always meant to be here,” he said.

Bartolini also explained that the government used the “Everglades Strategy” when the park was being formed because it didn’t have all of the needed funds to purchase the properties in the beginning. This approach allowed the government to “push the can down the road in terms of determining the ultimate disposition of the ranches.”

But Bartolini was quick to add that “It was clear from the record that [then-Park Service Director Conrad L.] Wirth wanted them out, as many others did. They never envisioned that ranches would stay.”

Finally, Bartolini made a point about the history of white privilege at Point Reyes: referring to the ranches as “historic” spites the local Coast Miwok Tribe whose ancestors are buried on the land and whose cultural and ceremonial sites inside the Seashore were used for millennia.

“It’s amazing that you have one-third of the park, 28,000 acres, going to glorify a history of white Americans that existed on this land for 150 years, when California has the largest Native population in the entire U.S. who’ve inhabited this land for 10,000 or more years and they’re getting one-and-a-half acres in the park to celebrate their history,” he said. “If that doesn’t say systemic racism, I don’t know what does.”

The Rancher: PRNS Ranching Families ‘Felt Safe’ the Deal Was ‘in Perpetuity’ When They Made ‘This Agreement’

Kevin Lunny is the head ranchman at Lunny Ranch — one of the 24 operations the elktivists want uprooted and removed. He defended his business and told EnviroNews his family’s operation in the park is small-scale and less invasive than the larger dairy operations. He said they run less than 100 organic, grass-fed beef cattle in the Seashore and that it would be “devastating” to his family if the government kiboshes his business. And it wouldn’t be the first time either.

Lunny’s family once owned another operation in the Seashore: the Drakes Bay Oyster Company. Again in this instance, conservation orgs sued and forced an environmental review. The result: the Department of Interior, under Obama’s Secretary Ken Salazar, shuttered the oyster company and ordered the area be restored to wilderness. In a November 2012 press release, Salazar said this:

I’ve taken this matter very seriously. We’ve undertaken a robust public process to review the matter from all sides, and I have personally visited the park to meet with the company and members of the community. After careful consideration of the applicable law and policy, I have directed the National Park Service to allow the permit for the Drakes Bay Oyster Company to expire at the end of its current term and to return the Drakes Estero to the state of wilderness that Congress designated for it in 1976. I believe it is the right decision for Point Reyes National Seashore and for future generations who will enjoy this treasured landscape.

Salazar, who was a rancher himself, was an advocate of continuing livestock operations in the Seashore, however, adding, “Ranching operations have a long and important history on the Point Reyes peninsula and will be continued at Point Reyes National Seashore.” But again, the question remains: Is ranching at the Seashore supposed to roll on and on in perpetuity or is it supposed to end?

Lunny expressed his views on that question in an exclusive on-camera episode, saying, “My understanding is [that all the ranching families] felt safe that this was for perpetuity. I understand that the language of the agreement doesn’t say ‘in perpetuity,’ but it doesn’t say it’s temporary either,” Lunny continued. “So, that’s been a big part of the discussion.”

Lunny told EnviroNews that he supports some of the measures to help wildlife in the new GMP though, such as having to install wildlife-friendly fencing going forward. He said he understands that logic and that he’s trying to get ahead of the curve, whereafter he showed EnviroNews producers some of the first wildlife-friendly fencing they had seen in the park thus far. The countless miles of non-wildlife-friendly fencing currently in place are allowed to remain under Alternative B, but Lunny claims due to the salty air and corrosion all the old fencing will be replaced within a matter of several years anyway.

At the time of the interview, Lunny said he didn’t fear the Biden Administration would pick a different direction in which draft alternative to select; he felt confident the agency would stick with Alternative B. And Lunny was right on that point. But he did admit he was concerned with what the outcome of the lawsuits could be [Editor’s Note: Update: five weeks after the publishing of this article, NPS was sued for its RoD on the Tule Elk GMP by WWP, RRI and the Center. The lawsuit is pending].

The Congressman: ‘You’re Not Going to Get Any Clarity on That Issue’

Whenever there’s a news piece, op-ed, protest or even a common conversation about the battle for tule elk and the Point Reyes National Seashore, there’s a high chance you’re going to hear one particular name come up: Representative Jared Huffman (D). As California’s “North Coast Congressman,” PRNS is in Huffman’s home district (2nd). When Huffman sat down on camera with EnviroNews earlier this year in a rare in-depth environmental exclusive, he complained that people were always trying to place him in the center of the Point Reyes saga — in his opinion, wrongly so, saying, “So, there’s been a bit of an effort to make it all about me, to lump me in with Rob Bishop and Dianne Feinstein, do all this crazy caricature; it doesn’t really fit.” But, why are so many folks protesting against Huffman over his stance on PRNS and the tule elk anyway? Why does he keep finding himself at the center of the conversation?

Huffman wound up in the spotlight over Point Reyes when he teamed up with staunchly conservative former Congressman Rob Bishop (R) of Utah and actually attempted to codify a plan for PRNS into law in Congress — something that outraged many of his environmental constituents — many whom have admitted publicly that they voted for him.

In the vast majority of cases, Congress leaves wildlife management and the administration of the Endangered Species Act to the USFWS and NOAA — both executive departments, charged with wildlife management in accordance with NEPA. As was pointed out in the interview, “It’s pretty rare to see Congress get involved in [the management of] imperiled species.”

So, what does the North Coast Congressman have to say about the notion of forever-ranching at PRNS? Of the many strong opinions EnviroNews has garnered on that question, Huffman took a different stance and said the waters are muddy and that it’s not possible to find “absolute clarity on that question.”

“I’ve poured through the congressional record and the legislative history,” he continued. “There is certainly evidence that some continuation of this multi-generational ranching was very much envisioned; there’s some evidence also that some wanted it to eventually go away. But it was unresolved.”

But even though the Congressman says there isn’t “absolute clarity” on the issue, he defends the continuation of ranching in the Seashore, nonetheless. He made it unapologetically clear to EnviroNews which side of the issue he comes down on. “I [understand] the history, I understand the mission of this unit of the National Park Service, which is not to make the entire Seashore wilderness. It’s a myriad of purposes and objectives,” he asserted.

Despite all the heat Huffman is taking over PRNS and the tule elk, he is still considered to be one of the most environmentally-friendly lawmakers in the House, even achieving a 99 percent environmental scorecard from the League of Conservation Voters. Still, he continues to draw ire and ridicule from the conservation movement over his position on Point Reyes and the Tule Elk General Management Plan. He’s been shouted down at town-halls repeatedly and blasted by prominent members of the community at rallies and all over social media. And even though the Congressman says NPS’ plan isn’t “perfect” he hangs tight in espousing the primary components of Alternative B. “It’s not a perfect plan in my opinion, it’s not my plan, but I think it does several important things.”

During Huffman’s interview with EnviroNews, in fairness, he was given the opportunity to “reverse corse” and “change his position” right then and there on camera. He declined, instead segueing to a statement about how all local politicians agree with him and want ranching at PRNS too.

It was only one day after the Huffman interview was published that former Petaluma City Councilman Matt Maguire called Huffman out in public. That happened at another protest — this time, in front of the elk fence that blocks the Tomales Point herd into a small peninsula with limited water and forage. By way of NPS’ management, 152 animals in this herd died last year, while the Seashore’s two free-roaming herds scarcely took a hit at all. “For a guy who is otherwise a really pretty good green congressman, he is wrong on this issue and he needs to change his position,” Maguire said in a drop-the-mic moment to uproarious applause and cheer.

Maguire introduced himself to EnviroNews producers at the protest and wrote this in a follow-up interview:

My eight years on the Petaluma City Council give me a good perspective on the government side of things. And I frankly don’t believe Huffman when he says every elected person in the area supports his position. I know that no city councilperson or county supervisor is going to piss off their congressman if they want to have a productive relationship with them, and Huffman knows that too.

Bartolini called out Huffman by name as well, chastising his position and Ken Bouley did the same. “I can’t really say as to why Jared Huffman is taking such a strident stance on this,” Bartolini said.

However, when Kevin Lunny was asked about “what kind of either support or opposition [he’s] received from [his] leaders in Washington,” he gave high praise and said, both Huffman and Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) have been “entirely supportive.”

Finally, Huffman was asked pointblank by EnviroNews: “Are you lifelong friends with any of these [ranchers] out there, do they lobby you, are they contributing to your political campaign?” To that, he responded:

Yeah, look, these are folks… No. I mean, they’re probably I’ve gotten some contributions from them. I am sure that it is a fraction of the campaign fundraising I do from environmentalists – I mean like a sliver. I get way more. In fact, some of the same people that are cursing me have donated to my campaign multiple times (laughs).

Huffman might squeak by with that statement, but campaign finance watchdog group OpenSecrets reveals that Huffman has received significantly more campaign dollars from the agribusiness sector than from environmentalists. According to its website, OpenSecrets is the “most comprehensive resource for campaign contributions, lobbying data and analysis available anywhere.”

AN OLD POINT REYES NPS SUPERINTENDENT GETS COZY WITH THE CATTLE INDUSTRY

When taking a deeper look at how the tradition of issuing extensions to the Seashore ranchers really got going, one name kept coming up: John L. Sansing. It’s common for high-ranking NPS officials to be bounced around the country from post to post, but not in the case of Sansing whose time atop Point Reyes NPS as superintendent lasted nearly 25 years. Park historians tell EnviroNews that Sansing had a special affinity for the area and did not want to be relocated.

Regarding Sansing’s tenure, NPS made these admissions through its own website:

Sansing was most effective in his work with the peninsula’s ranchers. He noted that his predecessor, [Edward] Kurtz, had done a good job developing relationships with the conservation community but had not paid enough attention to the ranchers. Sansing, on the other hand, made it a major objective of his administration. From the outset, Sansing went out of his way to foster a positive relationship between the park and the agricultural community… Likely, he also viewed the ranchers as an external base of political power, as several ranchers, most notably Boyd Stewart and Joe Mendoza, had strong ties with members of Congress.

Bartolini weighed in on Sansing’s long and controversial term as superintendent and he pulled no punches, telling EnviroNews this in a written interview:

In the modern-day history of the park, two people stand out for their contribution to making Point Reyes a monument to white privilege and all that has wrought in our society: John Sansing and Dianne Feinstein. Sansing used his authority as [an] NPS Superintendent, and Feinstein her authority as a sitting member of the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee that funds the Interior Department and NPS, to ensure that this would be a park not for all Americans, but a divided park.

Again, according to NPS’ website, “In a 2004 interview, Sansing acknowledged that although some of his actions created enough enmity that, on at least two occasions, he was very close to being transferred or demoted, he was able to utilize his political connections to get himself off the hook.”

Former NPS Park Ranger/PRNS Tule Elk Biologist under Sansing: ‘[Sansing] showed little interest in natural resource conservation… [his] decisions [favored] the ranching community’

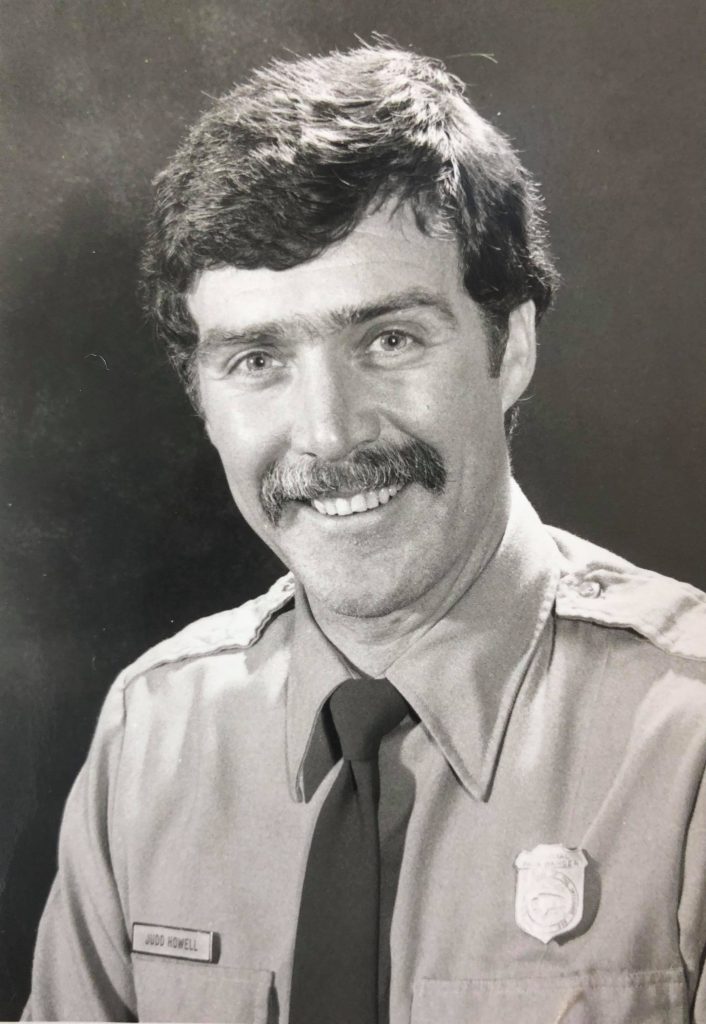

To explore Sansing’s activities a little further, EnviroNews reached out to someone who was around when the RUOs started being handed out: Judd Howell, PhD. Howell is a research wildlife ecologist and as the first park ranger for the nearby Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), he worked under Sansing in the 80s. In the mid to late 90s, Howell and his team conducted the research on the Pierce Point tule elk herd that was used in crafting the original 1998 Tule Elk General Management Plan.

In an editorial penned in the Marin Independent Journal, Howell wrote, “[Sansing] showed little interest in natural resource conservation, and his decisions at the time seemed to me, to favor the ranching community.” In a digital interview with EnviroNews, he added, “My understanding was that Sansing did not want to [be relocated] and that there was pressure from the ranching community to have him stay.”

Howell stops short of accusing Point Reyes NPS of all-out shenanigans back in those days though, clarifying, “I did not see signs of corruption, just poor management.” However, when asked if “the Point Reyes NPS unit espouses the same mission as other NPS units [he’d] observed?” and “Is its modus operandi in alignment with NPS’ mission as a whole?” Howell didn’t mince words. “At this point no, [Point Reyes NPS’ current approach is not in alignment],” he said. “The mission of the National Park System is to protect and preserve for use and enjoyment of the public, leaving it unimpaired for future generations. That is not what I see at Point Reyes.”

When asked if ranching should roll on in perpetuity at PRNS, Howell said no way:

I think ranching should be discontinued. They were paid a fair price, and the land belongs to the people of the United States. As stated in [our] letter to the Secretary of the Interior, my colleagues and I would rather see several thousand elk than 5,500 head of cattle.

The “letter” he’s referring to is one where he and several distinguished colleagues reached out to Haaland, urging the Interior to reject Alternative B and to change NPS’ strategy on PRNS tule elk management in multiple aspects, drawn out in detail. But like the letter from the Coast Miwok and the petition with more than 100,000 signers, it was crickets from the Secretary on Howell’s letter as well: zilch, nothin’, nada. He continues to keep the pressure on though, through his writings and actions.

Former NPS Lawyer: ‘No, no, no. Not Forever. Not at all, in Fact.’

Jim Coda is considered by many locals to be one of the foremost experts on PRNS — from both a legal and historical standpoint. Coda was a National Park Service attorney and he’s studied the PRNS issue extensively. He’s a local Marin resident and an avid hiker and wildlife photographer.

Like Howell, Coda didn’t hold back when calling out Sansing, noting the late-Superintendent was a transplant from Arizona who wanted to stay in the area and “wanted the ranchers to like him.” In an exclusive on-camera interview with EnviroNews, he added:

[Sansing] started giving [the ranchers] — without any other consideration about anything else — he started giving them five-year leases, maybe some 10-year leases, and permits as well as leases. And he started doing that and he kept doing it: five years here, five years there. And before you knew it, everyone thought: Well, the ranches are supposed to be here forever. But, they weren’t supposed to be here forever. There was nothing in the original legislation about the ranchers sticking around.

Continuing on that topic, Coda told EnviroNews this in a followup email:

The best evidence of intent is the 1962 law. It shows no intent regarding ranching. That’s how it got passed. [The bill] wasn’t’t going anywhere otherwise.

Since the original rancher RUOs were written into the deeds of sale, they couldn’t be reissued, leaving the ranchers in a tough spot. “They couldn’t repeat them because you can only buy a ranch once,” he said. “After that it would have to involve a lease.”

Coda’s perspective does bring up an interesting point: If ranching was supposed to go on forever at PRNS, why wasn’t that indicated in the original legislation? Why do the ranchers need special use permits at all?

“The 1978 [legislative] amendment gave Sansing the authority to issue ranching leases,” Coda clarified, but he said that would be contingent on other factors. “[Sansing] could only do it if ranching didn’t harm natural resources, as provided in the [National Park Service] Organic Act [of 1916] and similar language in amendments to the PRNS and GGNRA statutes.”

Coda’s legal opinion: the Point Reyes NPS unit is out of step. “I do believe NPS has been violating the three [PRNS/GGNRA] statues throughout the whole leasing process because ranching [has been] greatly harming the lands [and] waters for decades, in violation of the three statutes.”

Speaking of the land and water at PRNS, Coda showed EnviroNews multiple areas and ponds in the Seashore he said are highly polluted from ranch runoff. He also shared photos and resources he’s gathered in his countless hours walking the Seashore in his photography adventures. Some of those assets show the park’s tule elk being impeded — or worse — by non-wildlife-friendly cattle fences. This old-school fencing is a subject EnviroNews continues to document and investigate.

THE PEOPLE’S PARK?: PUBLIC COMMENTS AND FORM LETTERS: SHOULD THEY COUNT FOR ANYTHING OR NOT?

When examining the issue of whether livestock activities should continue long into the future at PRNS, it’s important to ask a couple of questions: 1) First, is the Seashore the people’s park? Yes or no? And, 2) If it is indeed the people’s park, should it matter what the public wants done with it? Melanie Gunn, Outreach Coordinator at Point Reyes NPS, says it’s not a democracy when it comes to the future of Point Reyes.

As the amendment planning process was being rolled out in late 2017, in a YouTube video, Gunn encouraged the public to weigh in, saying, “We want people to get engaged and get involved.” But after the public comment period was opened as part of the NEPA-mandated review process and over 90 percent of 7,627 commenters that “engaged” in the process favored removing all ranching activities from the park. In an article in the Pacific Sun, Gunn said this:

It’s not a popularity contest… One really important thing for people to realize [is] it’s not a vote. And we try to make that clear to people. What we’re looking for is substantive information to inform the process.

Erik Molvar, Executive Director of WWP, takes a different view, telling EnviroNews this in a digital interview:

Ranchers (or any other industrial interest group) don’t get to discount public comments because they express exactly the same sentiment. The overwhelming majority of Americans feel exactly the same way about Point Reyes: It’s time to get the cows off, and at least move them onto private lands. Ranchers are always whining about and pushing against the will of the majority, exposing an ugly reality: The ranching industry is a tiny and economically irrelevant (but highly privileged and highly entitled) minority in this country.

But Seashore rancher Kevin Lunny agrees with Gunn’s stance, and told EnviroNews that public comments are for the sole purpose of informing the process and that any copy/paste-style letters should only be counted once — this, after environmental groups circulated form letters that concerned citizens could attach their names to and send to NPS. “If you get 5,000 comments that are identical, that counts as one comment, under NEPA, under the law,” Lunny asserted to EnviroNews in an exclusive on-camera interview earlier this year.

But EnviroNews also spoke to the man who analyzed both the NPS comments and an additional 45,000 public comments that were turned into the California Coastal Commission (CCC/the Commission): Inverness resident Ken Bouley. He conducted that research on behalf of Resource Renewal Institute — one of the plaintiffs in the aforementioned lawsuit.

Bouley is a software architect with the Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO), and used a combination of techniques to scour the comments for data-points. He doesn’t see things the way Lunny and Gunn do. When asked in an exclusive on-camera interview with EnviroNews, “What happens if you take out all of those form letters, what does it look like then?” As an analytics guy, Bouley had a wealth of information to share on the topic, but held firm when explaining the comments were extremely lopsided in the direction of Alternative F — even with copy-paste letters gone:

We took every comment, we color coded it, and we put it up on a website. We published all our findings… So, if anybody doubts us, go and look, and have a peak yourself. And if you find 10 or 20, or if you find 100 that are miscategorized, you will not change the lopsided, landslide results anyways…

Just trying to be very conservative and not let my own bias get in the way, there may have been 1,000 or 1,500 letters that were repeated, but the the comments were 95 percent against Alternative B and in favor of getting rid of ranching in the park. So, you could pull out half of them… The fact is, there’s no way in which you can look at that data and dismiss what’s the obvious public sentiment, that people don’t want ranching in there.

Bouley also reminded EnviroNews viewers that the CCC comments were even more lopsided. Nevertheless, the CCC fell in line with NPS’ preferred Alternative B in a hotly controversial 5-4 “compliance” vote. It did so with only 12 (“not 12,000”) out of 45,000 comments being in alignment with the way the Commission voted. Bouley explained:

For the Coastal Commission, they actually did separate out form letters. So, that was very nice to us, because we did not read 45,000 pieces of correspondence… We actually tallied them up both ways: including the form letters, and excluding the form letters. And if you include the form letters — by the way, there were 12 letters, there were 12 pieces of correspondence in the 45,000 supportive of consistency (with NPS’ Alternative B) — not 12,000, 12. It’s amazing how it’s near unanimity.

If you take out the form letters, there’s about 400 individual pieces of correspondence to the CCC… So, it’s either 45,000 roughly to 12, or 390-something to 12. So, in other words, it’s either 99.95 percent against consistency and ranching in the park, or it’s about 95 or so percent against ranching in the park. That 95 percent is almost exactly the number that we got from the GMP comments. So, we’ve got here two large data-sets: 7,600, 45,000 — or 400, depending on whether you count form letters or not, and the numbers are just about the same.

So, then there’s Rep. Jared Huffman, who was also asked by EnviroNews about the statistical outcome of the public comment period. He was doubtful of the data and said he thinks the public actually favors ranching at PRNS. “So, all I can tell you is, you know, you referenced these statistics of 90 percent of the people want this and that and the other. I think you’ve got to be a little bit careful with that,” the Congressman said. “And it is not, I would say, a fair or comprehensive representation of public sentiment – certainly not in my district,” he continued.

But Huffman tried to cut the public’s voice out of the process entirely when he made a move in Congress that would have skirted a public comment period on Point Reyes all together — if it had been successful. He did this when he introduced H.R. 6687 with former House Rep. Rob Bishop — a bill that would have codified a plan for PRNS very similar to Alternative B. Bishop was loathed by conservationists during his tenure and is considered one of the most anti-wildlife, anti-public-lands lawmakers in modern times.

Wildlife management and status decisions are made primarily by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries), which are regulated by way of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA guarantees the public the opportunity to weigh in as a matter of record during the environmental review process. But that doesn’t happen when lawmakers get involved and meddle in what is supposed to be a science-driven process carried out by USFWS, NOAA and any other overlapping federal agencies.

Huffman was asked during the interview:

We know it’s not real common to see Congress get involved in imperiled species. We’ve seen it a few times: gray wolves, Yellowstone grizzlies, sage grouse, prairie chicken, some of these higher profile species. What [we] need to ask you about is your co-sponsor on this legislation: Rob Bishop… Why did you team up with him?

To those questions, Huffman responded:

Oh, [Bishop is] awful… It was not a partnership, first of all… He really does not like me. He hates me… The truth is, Rob Bishop chaired the Committee at that time. If I was going to pass a bill out of that committee, Rob Bishop was going to be the one that decided whether it left the Committee.

So, the area’s congressman attempted an end-around — a failed effort in the House that would have cut out public comments all together. Meanwhile, the ranchers and Point Reyes NPS say people’s comments shouldn’t count unless they offer something unique and informative. The environmental organizations say if a person takes the time and signs their name — even to a form letter — they are espousing that viewpoint and aligning their opinion with the form letter, and they say those comments do count.

WHAT IS NEXT IN THE BATTLE FOR POINT REYES?

The bottom of this investigative report has finally arrived, and so, are these ranches truly “historic?” To the Coast Miwok that notion is absurd. To officials, lawmakers and government agencies the historic argument provides expedient cover. To the PRNS ranching operations it’s the thread they hold on to for their very survival.

NPS’ mission statement reads:

The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.

If the argument is that these old ranches are needed to “educate” the public about “historic ranching” in the region, that notion too, has weaknesses, because the “natural resources” at PRNS are certainly not “unimpaired.” Additionally, the ranches and dairies at the Seashore have all been modernized; nobody is milking cows by hand into tin pales nor tilling their soil by oxen and plough. Both the educational and historical arguments are brought into question by that simple point alone.

Without the historic designation, it would be a difficult reach for the Interior to justify the presence of commercial agricultural operations within the bounds of a national park unit. And for most people, it’s not a happy hypothetical scene to envision dairies, oil wells or mining operations inside the Grand Canyon, Yosemite or Yellowstone. How does that prospect sit with the country’s citizens? Should industrial operations be allowed in America’s national parks at all?

And so, we come back to this: is PRNS the people’s park? If it is, extensive research conducted at EnviroNews would suggest a majority of the general public wants to see these ranches evicted without further ado. But if the park belongs to corruptible politicians, capricious secretaries and superintendents, agency politics and a unique NPS unit with a standalone agenda to protect and preserve a handful of agricultural profiteers, then ranching can, and will, continue in the park indefinitely.

Melanie Gunn and Kevin Lunny say that how the Seashore is managed in the years to come is not a “vote” and that most of the public comments shouldn’t even count. In any case, if the people of the United States want to see something different at the PRNS, they may have to shout very much louder from the mountain tops in order to make it clear who the Seashore belongs to and how it should be taken care of in the future.

FILM AND ARTICLE CREDITS

- Emerson Urry - Producer, Journalist, Author, Interviewer, Assistant Video Editor, Assistant Sound Editor, 3D Animator, Director of Photography

- Dakota Otero - Assistant Producer, Video Editor, Sound Editor, A Camera Operator, B Camera Operator, C Camera Operator

- Ian Burbage - C Camera Operator