Forest Service Prairie Dog Extermination Plan Could Cause Extinction of Black-Footed Ferret, Enviro Orgs Say; Lawsuit Filed

(EnviroNews Nature) — Washington D.C. — A lawsuit was filed against the U.S. Forest Service (USFS/the Service) on Nov. 18, 2021 by several environmental protection groups for a plan amendment the agency filed for northeast Wyoming’s Thunder Basin National Grassland. The NGOs say the move violates the Endangered Species Act (ESA) by threatening black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes) and black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus).

The lawsuit — filed by the Western Watersheds Project (WWP), Rocky Mountain Wild, and WildEarth Guardians (WEG/Guardians) — asserts the Forest Service’s plan to ramp up eradication of black-tailed prairie dogs by poisoning and sport shooting would harm the “keystone species that creates required habitat for many other types of native wildlife, including mountain plovers, burrowing owls, and swift foxes.”

The lawsuit also challenges the plan for its proposed elimination of a reintroduction area for black-footed ferrets that was previously designated to help recover the endangered animal.

Encompassing lands that are the traditional territories of the Cheyenne, Crow, and Lakota peoples, Thunder Basin (the Basin) has long been recognized by federal agencies as one of the most promising sites for ferret reintroduction due to the area’s large quantity of contiguous federal acres. The Basin also harbors many black-tailed prairie dog colonies — vital to ferrets for prey and shelter. But many landowners, livestock operators and state agencies consider prairie dogs to be pests that should be exterminated, and their war against prairie dogs has driven the black-footed ferret to the brink of extinction in the process.

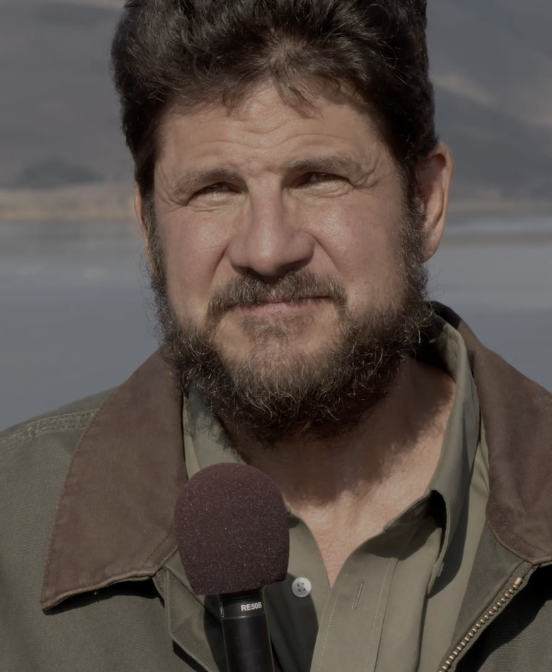

“The Forest Service has caved to pressure from ranchers and is embarking on a campaign of prairie dog poisoning and shooting,” said Western Watersheds Project’s Executive Director Erik Molvar in a press release. “If livestock are truly incompatible with prairie dog conservation and black-footed ferret recovery, the Forest Service should get rid of the cattle, not poison the native wildlife and eliminate habitat for endangered species’ recovery.”

Molvar says that ranchers have successfully chipped away at wildlife protections in Thunder Basin over the past two decades, with the Forest Service increasingly adopting their wishes over the objections of leading conservation groups. In an email to EnviroNews, he wrote:

Basically, the Forest Service switched over from a balanced approach in the 2002 plan that allowed livestock, prairie dog conservation, and ferret reintroduction to move forward side-by-side, to a plan that prioritizes the elimination of prairie dogs — a Forest Service sensitive species — to maximize the livestock numbers and convenience for the ranchers. They sold out the native wildlife for commercial operations on public lands, destroying the grassland ecosystem by design.

Pushed by agricultural interests and Wyoming state agencies, the new plan amendment would replace a 50,000-acre ferret reintroduction area with a 10,000-acre cap on prairie dog colonies and a management designation focused on livestock. This area would shrink lower still to just 7,500 acres during drought years, which have become ever more common in recent years due to anthropogenic climate change.

“The Thunder Basin amendment decision runs afoul of our national priorities and interests and instead nudges the black-footed ferret closer to extinction,” said Rocky Mountain Wild staff attorney Matt Sandler in the presser. Sandler also noted the decision goes against the Congressional prioritization of protecting imperiled species over local economic interests, required by way of the ESA.

WildEarth Guardians staff attorney Jennifer Schwartz was equally critical of the amendment decision. “The Forest Service has not only violated the legal requirements of the ESA and other federal laws meant to protect and recover this imperiled species, but also an ethical obligation to prevent the black-footed ferret from dwindling away entirely,” she opined.

WWP’s Molvar went on to note that Forest Service officials spoke up during the planning process, pointing out how the amendment would violate the agency’s requirement to maintain viable populations of prairie dogs and mountain plovers, while effectively preventing ferret reintroduction. The scientists were ultimately overruled.

“The bureaucrats ignored the objections of the biologists, in order to placate the commercial users,” Molvar contended to EnviroNews. “And the native wildlife and the public interest in healthy ecosystems and biodiversity lost out in the process.”

This lawsuit follows one filed by the same three NGOs in October that challenged the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) 2015 rule designating all future reintroduced populations of black-footed ferrets in Wyoming as “experimental” and “non-essential.” The groups say the designation deprives the ferrets of their full protections under the ESA while enabling the state’s agricultural agencies to expand their war on prairie dogs.

Molvar accuses both the USFS and the Cheyenne Office of the USFWS of being more concerned about “going along to get along with the livestock industry and its locally influential political allies” than doing their jobs to protect public lands and wildlife.

“In Wyoming, you often have to sue federal officials to force them to obey environmental laws and agency regulations, because otherwise they’re serial violators,” Molvar lamented.

Queried for comment on the lawsuit’s allegation that the amendment decision violates the Endangered Species Act, the Forest Service’s National Press Officer Babete Anderson told EnviroNews that the agency could “not comment on pending litigation.”

FILM AND ARTICLE CREDITS

- Greg Schwartz - Journalist, Author