HEALTH ADVISORY: Venison, Elk May No Longer Be Safe to Eat — Study: Deadly Chronic Wasting Disease Could be Moving to Humans

(EnviroNews DC News Bureau) — Alberta, Canada — Early results from an ongoing study testing human susceptibility to chronic wasting disease (CWD), a growing epidemic among deer and elk, has led Health Canada to warn “that CWD has the potential to infect humans.”

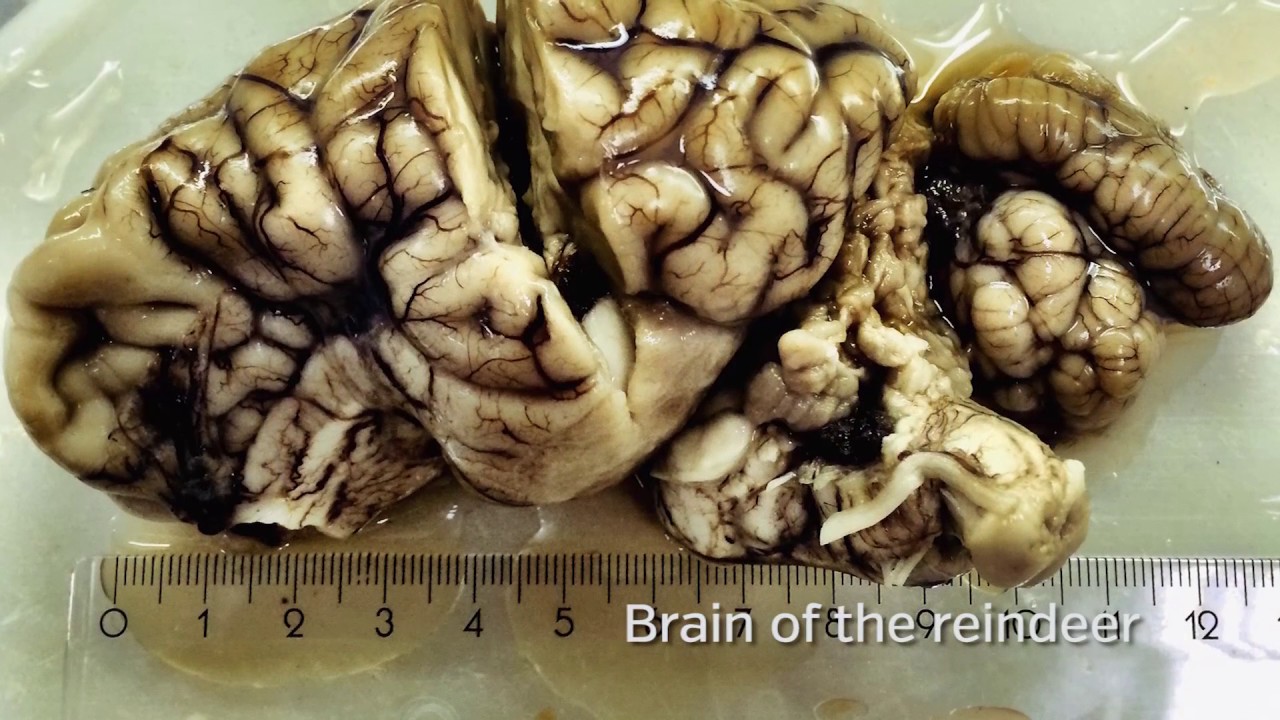

Chronic wasting disease is an incurable, inevitably fatal illness that can affect all cervids: deer, elk, moose and caribou. It is one of several prion diseases (pronounced pree-on), of which the most well-known is mad cow disease, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) identifies six known animal prion diseases and five that affect humans. The most common prion illness in people is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

In an advisory dated April 26, 2017, Health Canada cited a research project led by Dr. Stefanie Czub, head of the virology section at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), using cynomolgus macaques (Macaca cynomolgus). These primates are the closest to humans that can be used in medical research. “These findings suggest that CWD, under specific experimental conditions, has the potential to cross the human species barrier, including by enteral [oral] feeding of CWD infected muscle,” the advisory stated.

“The shockwaves are still reverberating through the scientific community because of this research,” said Darrel Rowledge, Director of the Alliance for Public Wildlife (APW), in a lengthy interview with EnviroNews. A former forester, Rowledge calls himself an activist and has been studying chronic wasting disease for almost 20 years. He’s visited the lab where the CFIA study is underway. “This is a wakeup call. These macaque data are stunning.”

Prions are abnormal, misfolded proteins. Lacking cell nuclei, they are not alive like bacteria, though they behave much like parasitic life forms as they replicate themselves by hijacking and misfolding otherwise normal proteins in the unfortunate host. They cause diseases that are collectively called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, or TSEs. Such diseases commonly infect the brain and spinal cord, and are nearly always undetectable until symptoms arise, often years or even decades after infection.

CWD was first identified in Colorado in the 1960s and has since spread to 24 states and two provinces in Canada. Small outbreaks have also occurred in South Korea and Norway.

It has long been believed that CWD is unlikely to infect humans due to the presence of a so-called “species barrier.” But BSE was also considered to be cordoned off until 1996 when Great Britain admitted, after years of denial, that mad cow disease had been transmitted to humans. Worldwide, 229 deaths have been reported. Those people were infected by eating meat or organs from disease-ridden cattle.

Previous studies on chronic wasting disease have hinted at the possibility of transmission to humans, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to recommend in 2012 that no “part or product of any animal which has shown signs of a TSE should enter the (human or animal) food chain.” Recent controlled laboratory studies have shown that other mammals can be infected with CWD. These include mice, voles, and squirrel monkeys. A 2012 study by researchers at Colorado State University found domestic cats susceptible to CWD infection.

“There’s always been a suspicion of the possibility, a hypothetical risk of transmission to humans,” Dr. Ryan Maddox, an epidemiologist with the CDC, told EnviroNews. “It’s something CDC has been keeping an eye on for a number of years.” But the new CFIA study adds further concern.

Begun in 2009, Czub started with 21 macaques, all females two and a half years old. Three were designated as negative controls while 18 were infected, or “challenged,” as scientists prefer to say, with CWD. Five were infected orally, two through the skin and nine directly into the brain. Three animals received intravenous injection of blood from other CWD-challenged macaques. Of the 21 animals, 10 are dead so far, including one of the three control specimens, which was euthanized for purposes of the study.

As some of these macaques became sick, they developed anxiety and tremors. Researchers reported that they began to lose control of their bodily movements. Four of the animals began wasting away, with one having lost one-third of its body weight in less than six months. Post-mortems and other tests have been completed on five macaques so far. Under the microscope, the tissue samples showed damage typical of malformed prion proteins, primarily in the spinal cord and brain.

“We felt that these results should be communicated,” Czub told EnviroNews in a detailed phone interview. “It teaches us really something about the species barrier.” She explained that BSE, or mad cow disease, showed up mainly in the spinal cords of macaques during earlier experiments, “and it seems to be the same in chronic wasting disease.”

What most surprised the researchers was the short length of time it took for some of these test animals to show signs of disease. The earliest onset was four and a half years — the same amount of time that cynomolgus macaques need to develop infection from BSE. “It should have taken longer for CWD,” Czub said.

One of only six experts certified by the World Organization for Animal Health to head a BSE Reference Laboratory, Czub was born in Marburg, Germany to parents who were both veterinarians. She earned her doctoral degree in Berlin where she first became involved in researching prion diseases. Czub gained more experience in the field at the National Institute of Health in Montana. In addition to her position at the CFIA, she teaches at the University of Calgary and has published many papers on prion diseases.

While most scientists would wait for the completion of their study and then submit the results to a peer-reviewed journal, Czub and her colleagues felt they couldn’t wait. “This whole experiment was done to generate data for a risk assessment of chronic wasting disease, and a risk assessment is always to protect human health,” Czub explained. “What we have so far is important enough to communicate it.”

The information was presented to the Canadian health authorities by the Alberta Prion Institute, which is funding the study. Health Canada, an organization described as “responsible for helping Canadians maintain and improve their health,” responded with its risk advisory.

EnviroNews asked the Public Health Agency of Canada, a separate arm of the Ministry of Health, for its response. In an email reply, Anna Maddison, Senior Media Relations Advisor, stated, “Initial results from a Canadian-led research project suggest that chronic wasting disease (CWD) is transmissible to non-human primates, specifically macaque monkeys. Although these findings are scientifically significant, the implications for human risk are not yet clear. The study is ongoing, and the final results must still be subjected to formal expert peer review.”

Rowledge demurred. “There is clearly a disconnect between policy and science,” he said. “We have been, at a fundamental level, ignoring some of the basic rules of science and epidemiology for years.”

A 2017 whitepaper published by the APW explains, “Prions are extremely resilient, known to resist disinfectants, alcohol, formaldehyde, detergents, protein enzymes, desiccation, radiation, freezing, and incineration [at greater than] 1100°F.” The paper, now being revised in light of Czub’s findings, was co-authored by Rowledge along with experts from the University of Calgary, the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board and Canada’s National Wildlife Disease Strategy.

“CWD is very, very challenging,” Czub sighed. According to the APW whitepaper, chronic wasting disease now represents “the largest bio-mass of infectious prions in global history.”

“This is not just an issue that matters to people who care about wildlife,” Rowledge added. “This matters to everyone.” That’s because approximately 75 percent of new human pathogens in the past 25 years have originated in animals, according to a 2009 British study. That study goes on to note, “Greater risks to human health from wildlife pathogens appear to be inevitable as a consequence of increasing human contact with wildlife through greater access to, and disturbance of, wildlife habitats.”

CWD is believed to have originated in Colorado, likely in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in the 1960s. It has expanded both geographically and to other cervids through exportation of infected herd animals, the environment and even through plants. Where deer or elk are highly concentrated, the infection can spread rapidly. A 2004 study by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln found that CWD migrated to Canada from the U.S. through a game farm in Saskatchewan. The disease spread from there to other game farms and to animals living in the wild. Game farms, artificial feeding and baiting encourage the spread of chronic wasting disease.

The Alliance for Public Wildlife estimates that 7,000-15,000 CWD-infected animals are consumed in North America each year. Rowledge explained they derived that figure through statistical analysis of deer populations in infected areas, the prevalence of infection and the number of animals harvested by hunters. But he cautioned that as state governments have cut back on testing, lack of hard data makes precise numbers difficult.

Testing of deer and elk kills is mostly voluntary, and usually comes at the request of hunters only when they suspect a diseased animal – typically from signs such as drooling or emaciation. “It’s not just that we don’t have enough precautionary measures to stop people from eating [these animals]; it’s that we’ve failed fundamentally to follow science and evidence in terms of containing the epidemic,” Rowledge said.

In the U.S., Colorado, Wyoming and Wisconsin are considered the hotspots for chronic wasting disease. According to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, “about half of Colorado’s deer herds and one-third of [its] elk herds are known to be infected with CWD.” This year, the state instituted mandatory testing in some areas.

Wyoming is in danger of losing its entire deer population to CWD. A 2016 University of Wyoming (UW) study of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) herds in the state, published in Plos ONE, found a 10 percent annual decline in the population of these herds, with the likelihood they would be wiped out in less than 50 years.

At least three cases of CWD-infected deer have been reported in Pennsylvania this year. In Wisconsin, one in eight deer in a single CWD-prone area tested positive in 2016. More than 65,000 animals killed in that region went unexamined, while testing in the state as a whole declined from 30,272 animals in 2002 to 6,129 in 2016.

Hunters, it seems, are more likely to kill infected deer. The UW study found that CWD-positive animals were over-represented in the harvest, possibly because infected animals change their behavior and react more slowly. But those subtle changes may not be apparent to the hunter, leading them to skip testing and possibly consume tainted meat.

“This is where it becomes really concerning for human health,” said Czub. “The muscle tissue we used [in our experiment] was from white-tailed deer, from a farm population in Saskatchewan and those animals did not show clinical signs [of CWD].” They would have appeared healthy to the average hunter.

Most states downplay the risks to people with statements like the one published in a pamphlet for hunters by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department that reads: “There is currently no evidence that CWD is transmitted to humans.” Colorado states: “Currently, there is no evidence that CWD poses a risk for humans; however, public health officials recommend that humans avoid exposure to CWD prions.” The Wisconsin Bureau of Wildlife Management website reads, “There is no strong evidence that chronic wasting disease (CWD) can be passed to humans.”

The World Health Organization, in an overview of prion illnesses, says, “No human case has been linked so far to these animal diseases.” The CDC, on its web page about CWD, states, “To date, no strong evidence of CWD transmission to humans has been reported.” The written response we received from the Public Health Agency of Canada echoes the same line: “At this time, there is no direct evidence to suggest that CWD may be transmitted to humans.” These organizations all recommend that hunters take precautionary measures when handling their kills and have suspected animals tested. But that may not be enough.

Diseased animals can harbor CWD prions for years without showing any signs. There is no diagnostic test short of a post-mortem to detect infected specimens. “A singular event can become a massive problem,” warned Rowledge. “In the case of BSE [mad cow disease] going to people, it was extremely unlikely, but 229 people lost that lottery.”

“At this point our recommendation is for hunters to strongly consider testing in situations where they may be hunting in an area where CWD has been identified in the cervid population,” said Ryan Maddox of the CDC, adding, “We’re looking into how we might revise that in the future.”

Of particular concern are indigenous populations who may rely on wild game for a large portion of their meat protein. Authorities in Canada contacted First Nations immediately following the release of the CFIA study data.

But what if you don’t hunt and don’t eat venison or elk? Can CWD still find its way into your home?

In 2009, researchers in Wisconsin watched 40 deer carcasses and 10 gut piles to see which scavengers took an interest. There was a surprising find: “Domestic dogs, cats, and cows either scavenged or visited carcass sites, which could lead to human exposure to CWD,” stated the study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Cats were shown to be susceptible to chronic wasting disease in a separate 2013 study published in the Journal of Virology. These researchers concluded “that the ingestion of and/or open wound exposure to CWD-contaminated material could cause feline TSE disease.”

What you feed your cat or dog might be worrisome too. Pet food contains “meat by-products” which, according to PetMD, can include diseased livestock. A 2013 investigation by Slate found that zoo animals, euthanized shelter animals and road kill all go to rendering plants, where they are ground up, cooked and then sold to pet food manufacturers. More than one million deer are killed in vehicle collisions in the U.S. each year. Wyoming, a known hotspot for CWD, made the top-10 list of states where a driver is most likely to strike a deer, according to insurance industry statistics. At these rendering plants, large cookers heat the raw ingredients to between 250 and 275 degrees for 90 to 180 minutes, according to an EPA document. But prions are known to resist destruction at temperatures four times that high.

Deer antler velvet, which the CDC found to contain chronic wasting disease prions, is now a popular nutritional supplement. It’s being used as a performance enhancer by athletes, and sellers claim it promotes muscle strength, energy and endurance. Dr. Andrew Weil, a practitioner of integrative medicine, writes, “I know of no scientific evidence to support any of the marketing claims made for these supplements.” The CDC warned, “Our studies indicate that antler velvet represents an additional source for human exposure to CWD prions.”

All of these avenues of possible exposure worry Rowledge. “We have to stop the movement of live animals, we have to stop the movement of product, we have to stop the movement of equipment from these game farms, we have to stop hunters from moving positive animals out of CWD areas.”

Both Canadian and U.S. authorities say they are taking steps to look for any indication that chronic wasting disease may have spread to humans in any form. So far, they’ve seen none. Maddison wrote to EnviroNews, “The Public Health Agency of Canada, in collaboration with Canadian health professionals and healthcare institutions, conducts ongoing national surveillance for all human prion diseases in Canada.”

Maddox explained that the CDC works with the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center at Case Western Reserve University to review “unusual cases” of human prion disease. Autopsies are performed and brain tissue examined. They look at cases from Colorado and Wyoming, where CWD has been endemic for decades. They also examine younger prion disease victims because the most common human prion disease, CJD, shows up primarily in older adults. Any similar disease in younger patients would raise a red flag. Aware of Czub’s new findings, Maddox said, “We’re paying close attention to this study and keeping track of what’s going on in the human population in this country as far as prion diseases go.”

There are caveats to Czub’s research, which she freely admitted. It is in-progress research, and the complete results will not be in for a few years. The study won’t be published in a peer-reviewed science journal until then. Additionally, two of the macaques in her study had diabetes, which Czub explained, lowers the level of insulin in the animal. Insulin is known to have a protective effect on neurons in the brain, thus potentially making them more susceptible to infectious prions.

But her study, which is funded at least through 2018, raises important questions about the potential for chronic wasting disease to show up in humans. She told EnviroNews that the scientific community may be overestimating the strength of the species barrier. “It’s something which I think we will need to be really dealing with.”

Rowledge was more blunt. “I don’t know what part of this isn’t a disaster unless we get in front of it.”

OTHER REPORTS ON PRION DISEASE BY ENVIRONEWS:

Invasion of the Zombie Elk – Chronic Wasting Disease Spreading Fast, Nearing Yellowstone Herds

(EnviroNews Nature) – In the late 1980s, farmers in Great Britain started to notice their cows stumbling around, acting strangely and losing weight. The problem got continually worse, until in 1993, more than 36,000 cattle in the UK died in a single year from mad cow disease. Prior…

PRION BOMBS! – Physicians Group Says Stericycle Undoubtedly Releasing Deadly Prions and Radiation

(EnviroNews Utah) – PRION: a word that many have never even heard before, but little do they know that this deadly and virulent “pest” may be lurking right on their dinner plate, or inside their cute little pets Fluffy and Rover, or even right in dear ol’ Gramma’s…

Dr. Tyler Yeates MD Calls Out Stericycle For Incinerating Deadly Brain-Attacking Prions Into the Environment – Stericycle Owns Up to it!

(EnviroNews Utah) – North Salt Lake City – In a shocking admission Thursday night at a heated town hall meeting, a VP from Stericycle has admitted that the company is allowed to accept and burn deadly and arguably indestructible brain-destroying prions at its North Salt Lake incineration facility…

Dr. Brian Moench of UPHE Discusses the Potentially Deadly Burning of Prions by Stericycle Medical Incinerator

(EnviroNews Utah) – Following Stericycle’s simply flabbergasting admission last Thursday night where they acknowledged that they are allowed to accept and burn deadly and largely indestructible prions, protestors took to the streets outside one of the country’s last standing hazardous medical waste incineration plants. Prions are the malformed…

Amy Uchida, 4th Year Medical Student at the U of U, is Asked About Stericycle’s Incineration of Deadly Prions

(EnviroNews Utah) – According to documents on the Department of Environmental Quality website, Stericycle’s permit needs to be renewed by August 19, 2013. The company’s current permit expires on Feb. 19, 2014. Regg Olsen is listed as the contact at the Department of Air Quality (DAQ) in charge…

FILM AND ARTICLE CREDITS

- Dan Zukowski - Journalist, Author

- Emerson Urry - Story Editor