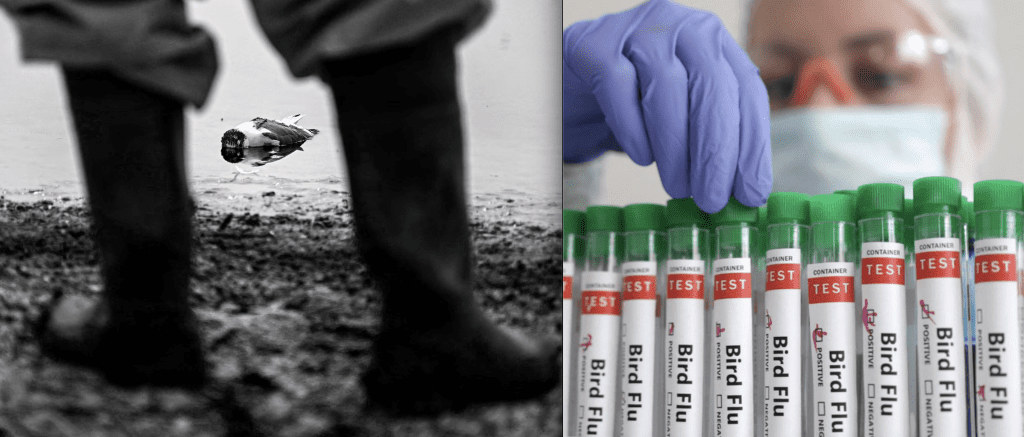

Bears Going Blind, Eagles Falling from the Sky as New H5N1 Bird Flu Wreaks Havoc in U.S. and Canada — Are Humans Next?

(EnviroNews Nature) — A strain of avian influenza known as H5N1 is now thought to have killed more than 58 million birds across the United States while hopping over the so-called “species barrier” and infecting 12 species of mammal. After originating in Europe in the fall of 2021, the virus travelled across the Atlantic to Canada and slowly moved through the U.S., quietly leaving untold suffering and devastation in its wake.

Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) have been blinded while snow geese (Anser caerulescens) were left unable to fly. Meanwhile, chickens have been culled by the millions leaving agricultural livelihoods destroyed. But how much worse can it get? Could a chicken-borne virus which travelled all the way from Europe to America and Asia to infect seals and foxes, eventually find its way to into humans?

David Stallknecht, a wildlife biologist at the University of Georgia, has been studying the virus’ journey and has noticed several quirks with this particular strain. Earlier in the month he explained to The Atlantic magazine how, unlike previous outbreaks of bird flu, this particular iteration is “better adapted to wild birds,” including migrating waterfowl such as ducks and geese. In turn, these birds can transmit the disease over huge distances and infect enormous populations.

Interestingly, some dabbling ducks such as mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) and northern pintails (Anas acuta) are able to carry the disease without suffering all that many symptoms. While this is great news for them, the flip-side is they unwittingly act as super-spreaders, passing the virus via their feces to large numbers of birds compared to other species which often die off quickly.

This flu’s penchant for wild birds — as compared to previous strains, which have largely affected poultry — means resident species such as black vultures (Coragyps atratus) and mute swans (Cygnus olor) are now succumbing to the disease. Meanwhile, icons such as bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) have been observed unable to stand up and fly, with some spotted plummeting out of nests and another 36 found dead. All in all, this is pretty grim news for U.S. wildlife. “We all have to believe in miracles, but I really can’t see a scenario where it’s going to disappear,” Stallknecht told Reuters.

So, if the end is not in sight, where does this all end? After all, the virus has already trickled into mammalian populations. Foxes, mink, seals, whales and bears have contracted the disease after apparently feeding on dead flu-stricken birds. While there is no evidence mammals have been passing it between one another, the growing tentacles of this virus have led to harrowing accounts of suffering. Three young grizzly bears were euthanized last fall after researchers found them disoriented and going blind. Wendy Puryear, a molecular virologist at Tufts University, told The Atlantic that infected seals are often found convulsing so badly they are unable to hold their bodies straight and die within days.

The spread of the virus to warm-blooded animals has fueled fears that humans could be next. While most scientists maintain the risk of spread to people is low, each detection in a new mammal hints the disease is improving its ability to jump to new hosts.

Richard Webby, a virologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital told The Atlantic this:

Every time that happens, it’s another chance for that virus to make the changes that it needs. Right now, this virus is a kid in a candy store.

The Paris-based World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) agrees with this dire prognosis. When asked about the virus’ transmission to mammals, the organization’s head of science, Gregorio Torres, told the BBC:

It could also be an indicator there is a change in the epidemiology of the disease or a change in the dynamic of the disease. And that will require close monitoring.

There is a risk for further transmission between species and we cannot underestimate the potential adaptation to humans. The disease is here to stay at least in the short term.

But while the World Health Organization (WHO) still categorizes the risk of transmission to humans as “low,” the effect on people is still palpable. The culling of millions of chickens has led to a worldwide shortage of eggs while some farmers have been left bankrupt.

Kishana Taylor, a virologist at Rutgers University, points out that the world is already facing catastrophic declines in wildlife — particularly birds. But other animals such as coyotes and snakes might go hungry, while the fish, insects, and rats that birds eat could experience population booms, altering the biodiversity landscape for good.

Nicole Nemeth, a veterinary pathologist at the University of Georgia, says some locals in the Southeast have even pointed to roadside deer carcasses beginning to fester in the sun because of an absence of vultures.

However, there is some hope. While vaccinating birds against flu is difficult to pull off, there are glimmers of success. According to the vaccine alliance known as Gavi, China began mandatory vaccination of poultry against an H7N9 strain in 2017 that was able to spread to people. This massively reduced the spread of the virus in birds, and eventually cut the number of human infections to zero.

Sadly, the current strain is proving very tricky because it infects more species of bird. Public health officials also fret because they say if a vaccination program were to be carried out hurriedly without proper testing that it could merely allow the virus to circulate at a low level, actually increasing the chance of mutations and spreading to people.

FILM AND ARTICLE CREDITS

- Dan Keel - Journalist, Author